June 30- A Word about Erasure

We have arrived at the end of the month, and over the course of the past 30 days we have been introduced to stories about a wide range of queer people from history. Some were closeted, others were not; some were names that would be familiar to many SCAdians, while others were probably new to many readers. We have covered poets and prostitutes and persecutions and all points in between, but before we sign off on this Pride Project, there is one more topic that I would like to address: erasure.

Erasure is the removal of queer people from various historical records, or downplaying queer people’s significance in history. This also connects to the false idea that heterosexuality Is the “norm,” a standard by which human existence should be measured. If persecution was a common theme in many of the posts this month, erasure is a more insidious way of denying queer existence through history. It happens in many ways, including straightwashing, which is when queer relationships are recast as heterosexual ones in a written or pictorial record. This happened with retellings of the life of Alexander the Great. Despite being a historic figure known to have lovers of multiple genders, some versions replace his male lover Bagoas with a female version instead, swapping his gender both in the text and the painted miniature accompanying it.

That is just one of many examples of queer erasure from the period we recreate. There are likely countless others we may never know about because their names and stories have not survived into the 21st century the way that Alexander the Great’s have. In the SCA, where we strive to recreate the Middle Ages “as they should have been,” whether you are a member of the queer community or an ally, I would suggest that it is our responsibility to keep the names of these people alive. Share their stories, remind the naysayers that queer history is, in fact, a part of our period, and make sure we do not stand by and allow queer erasure to continue into these Current Middle Ages.

~Maistresse Mariette de Bretagne, OP (she/her)

Deputy Minister of Arts & Sciences for Education

June 29- Usuegi Kenshin

Usuegi Kenshin was a famous Sengoku period daimyo in 16th century Japan. Known as “The Dragon of Echigo” for prowess on the battlefield, Kenshin was also a respected politician and skilled administrator who worked to improve the lives of the people in the province. Today, Kenshin’s name is also tied to the “Female Uesugi Kenshin” theory (上杉謙信女性説), proposed in 1968 by historical novelist Tomeo Yagiri, which claims that Kenshin was secretly a woman. Yagiri bases his theory on two primary points: the uncertainty surrounding their cause of death and the feminine depiction and references to Kenshin’s life.

On the 9th of March, 1578, Kenshin collapsed suddenly and fell into a coma, dying a few days later. The cause of death was believed to be a cerebral hemorrhage, as the fall and subsequent coma would suggest.1 However, a letter reporting Kenshin’s death claims that what caused him to fall in the first place was “mushike” (虫気), a broad term for intense abdominal pain of various causes.2 In Toudaiki (当代記) or “Current History”, a collection of diary-style historical records believed to have been compiled by fellow daimyo Matsudaira Tadaaki (松平忠明) around 50 years after Kenshin’s death, the cause of death is instead recorded as “oomushi” (大虫) or “big bug”.3 Yagiri explains that “oomushi” was a feminine term for red miso and was sometimes used among women to allude to menstruation or other uterine bleeding. Because Kenshin was also reported to suffer from recurring abdominal pain during battle, Yagiri theorizes that complications related to menstruation, such as uterine cancer, might be the true cause of death, or at least a contributing factor to his sudden collapse.4

Depictions and references to Kenshin also tend to indicate a female person is being portrayed or discussed. For example, Yagiri cites a song circulating among the people that refers to Kenshin as “a peerless power that even a man can’t reach” (男もおよばぬ大力無双), suggesting that the specific wording calls his gender into question.5 However, the specific wording also carries a Buddhist connotation in line with the prevailing belief among Kenshin’s followers that he was an avatar of the Buddhist god of war, Bishamonten.6 Yagiri also cites a report that he claims to have personally found in a monastery in Toledo from a “Gonzales of Spain” to King Philip II that references an aunt of Kenshin’s nephew. As Kenshin was his sister’s only sibling and did not have a wife, Yagiri suggests this must have been a reference to Kenshin, and that the Spanish saw Kenshin as a woman. However, Yagiri does not provide a name for this monastery, and the report has not been verified by anyone else.7 There is no proof of Kenshin having a wife, concubine, biological children, or any relations at all, only tales. Kenshin was also the only man allowed to interact with the emperor’s harem unsupervised. Though this is commonly attributed to Kenshin’s Buddhist vow of celibacy, Yagiri believes it to be further evidence in support of his theory.8

Despite a general lack of academic support for Yagiri’s theory, the mystery surrounding many aspects of Uesugi Kenshin’s life and the frequent depiction of a female Kenshin in popular culture continue to inspire debate among fans of the period, and rumors abound about the whereabouts of the body (some theorists claim that it was moved to prevent a closer examination which might reveal Kenshin’s gender.) For further reading on the more speculative aspects of the Female Uesugi Kenshin Theory, forum threads and blog posts abound in both English and Japanese. Were Kenshin alive today, we might consider them to be genderfluid or transgender, or we may have discovered that they were intersex, but in the 16th century, for a relatively high-ranking noble, such terminology was not an option.

Sources:

1. Sakae Ono, Yonezawa-Han (Tōkyō: Gendai Shokan, 2006), p. 62.

2. Itō Jun and Masahiko Naishi, Kantō Sengokushi to Otate No Ran: Uesugi Kagetora Haiboku No Rekishiteki Imi Towa (Tōkyō: Yōsensha, 2011), pp. 163-165.

3. Tsuneo Nanba, “Toudaiki,” Shiseki Zassan, vol. 2 (Tōkyō: Kokusho Kankōkai, 1911), pp. 1-215, https://dl.ndl.go.jp/info:ndljp/pid/1912983/7?itemId=info%3Andljp%2Fpid%2F1912983&contentNo=7&__lang=en.

4. Tomeo Yagiri, Uesugi Kenshin Wa Onna Datta (Tōkyō: Sakuhinsha, 2002).

5. Tomeo Yagiri, Warera Nihon genjūmin (Tōkyō: Shinjinbutsuōraisha, 1970).

6. Ōta Gyūichi, Elisonas J S A., and Jeroen Pieter Lamers, in The Chronicle of Lord Nobunaga (Leiden: Brill, 2011), p. XV.

7. Tomeo Yagiri, Intoku No Nipponshi (Tōkyō: Nippon sheru shuppan, 1982).

8. Uesugi Kenshin No shōgai, 6. Shin Jinbutsu Ōraisha, 1988. https://books.google.com/books?id=PZcyAQAAIAAJ&focus=searchwithinvolume&q=%E5%A4%A7%E8%99%AB.

~Lord Jaspar van Doorne (he/him)

June 28- The Cut Sleeve

Emperor Ai of Han was an emperor of the fabled Chinese Han dynasty for six years. In those six years, Emperor Ai was viewed as intelligent, capable, and articulate. He was also viewed as corrupt and tyrannical due to the heavy influence from his grandmother. However, Ai was also known to be quite the romantic according to traditional historians.

Circa 4 BCE, Ai began to favor a minor official, Dong Xian. Historians believe that, even though both men were married, they had a homosexual relationship. Indeed, Ai came from a long line of emperors, all of whom were married, with male companions listed in their official histories. Dong and his wife moved into the palace and Dong’s sister may have become an imperial consort. Further favor was shown in that Dong’s father was made an acting marquess. Emperor Ai also ordered that a residence as lavish as an imperial palace be built for Dong. Dong, himself, was noted for his relative simplicity contrasted with the highly ornamented court and was given progressively higher and higher posts as part of the relationship. Eventually, Dong became the supreme commander of the armed forces.

There is a short story that also demonstrated Ai’s love for Dong by Pu Songling called Huang Jiulang, which when translated into English is “Cut Sleeve.” The story alludes to Emperor Ai’s romantic relationship with Dong Xian where, after a night of drinking they fall asleep next to each other. When the emperor is awakened to attend to Court business, he cuts off his sleeve which is trapped underneath a sleeping Dong so not to awaken him. In doing so, Ai demonstrated quite a romantic gesture since the Emperor’s clothing was very expensive to create.

Unfortunately for the two lovers, their relationship was short lived. A short three years after the beginning of their relationship Ai died due to an illness. On his deathbed, he ordered that the throne be passed on to Dong (which was completely ignored by imperial counselors). Upon Ai’s death, Dong Xian and his wife committed suicide. Emperor Ai’s abuse of power, first influenced by his grandmother and then by his love for Dong, caused the people and the officials to yearn for the return of the Wang Clan. All that remains of Ai and Dong’s tale is the lasting imagery of seeing your love fast asleep and, as to not disturb them, a single sleeve remaining acting as a pillow, though the single cut sleeve lives on in Asian street fashion among queer youth as a subtle way to express their sexuality.

Sources:

- “Emperor Ai of Han.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emperor_Ai_of_Han#The_rise_of_Dong_Xian

- Hinsch, Bret. (1990). Passions of the Cut Sleeve. University of California Press.

- Stern, Keith. (2009). “Ai Ti.” Queers in History, BenBella Books.

~kasumi no tanaka, OP (she/her) & Viscountess Sefa Hrafnsdóttir, OP (she/her)

June 26- Ashikaga Yoshimitsu

Nanshoku (男色) meaning “male colors” was used to describe male homosexual interactions in the pre-modern eras of Japan. One of the more prevalent places Nanshoku occurred was in Buddhist monasteries. Ashikaga Yoshimitsu, the third shōgun of the Ashikaga shogunate formerly named Haruō, was sent to a Buddhist monastery prior to being named shōgun at the age of ten. Once he reached adulthood, he quickly became a powerful shōgun and was greeted by many emperors and kings of other nations. He was also entitled to all forms of entertainment which is how he met Zeami Motokiyo, his “Beloved Retainer.”

Zeami Motokiyo was raised in a Noh theater ensemble started by his father. Zeami was found to be a skilled actor and as the popularity of Noh and his father’s ensemble grew, Zeami was invited to perform in front of the shogun Yoshimitsu. Impressed by his skill, Yoshimitsu and Zeami began to have a love affair with him and became his beloved retainer. Through the shōgun’s patronage and love, Zeami acquired an education in literature and philosophy which gave him the tools and knowledge to go on to write between 30 to 50 Noh plays. Zeami being an educated actor was something not known at the time due to an actor’s designation as a member of the lower class, which also led to some controversy in the imperial court.

Alas, all was not always well between Zeami and Yoshimitsu. Zeami spent a lot of time trying to surpass a rival actor favored by the shōgun named Inuo. Once Yoshimitsu passed away at 49 in 1408. Zeami found it hard to gain favor with the new Ashikaga shōgun Yoshimochi. He was exiled to Sado Island in 1434 but was eventually pardoned and returned to the mainland to eventually pass away in 1443.

Yoshimitsu and Zeami’s relationship was one of many Nanshoku relationships in the pre-Meiji era Japan and helped sculpt and solidify nanshoku relationships in the future which lead to the writing of the Saiseki (Silkworm hatchling), a guidebook written in a Buddhist temple in 1657 which was a guide for proper behavior in nanshoku relationships.

By the late Tokugawa era and leading into the Meiji era, western culture seeped into Japan and so did the scorn and condemnation of homosexual relationships. Though homosexuality was only officially criminalized for 8 years in Japan (from 1872-1880), same-sex couples are still not afforded the same rights and protections that those in heterosexual relationships enjoy in modern-day Japan.

Sources:

- Furukawa, Makoto. The Changing Nature of Sexuality: The Three Codes Framing Homosexuality in Modern Japan. pp. 99, 100, 108, 112.

- Childs, Margaret. (1980). “Chigo Monogatari: Love Stories or Buddhist Sermons?”. Monumenta Nipponica. Sophia University. 35: 127–51.

- Stavros, Matthew, and Norika Kurioka. (2015). “Imperial Progress to the Muromachi Palace, 1381: A Study and Annotated Translation of Sakayuku Hana”. Japan Review 28: 3–46. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43684115

- Crompton, Louis. (2003). Homosexuality and Civilization. Harvard University Press. p. 424.

~Lord Albrecht Anker (he/him)

June 24- Aelia Eudocia

Aelia Eudocia (nee Athenais) was the wife of Byzantine Emperor Theodosius II and the daughter of Athenian sophist Leontius. She received the best classical education available and was an accomplished poet at a young age. She impressed the young Theodosius’s sister Pulcheria so much with her erudition that Pulcheria convinced her brother to marry this daughter of a minor family from a city that had seen better days. They were married in 421 CE in Constantinople.

Eudocia bore two daughters to Theodosius. The elder daughter Licinia Eudoxia would marry Valentinian III in 437, which secured an alliance between the eastern and western empires. The following spring, Eudocia went on pilgrimage to Jerusalem, without her husband, which has fueled much speculation about this trip and about her eventual exile from Constantinople. She funded public works along her journey through Antioch and Jerusalem proper. She traveled often in the company of Melania the Younger, a Christian ascetic who would later become venerated as a saint.

Upon her return to Constantinople, Eudocia found herself estranged from Theodosius and his inner circle. The court eunuch Chrysaphius was not fond of the empress, whose reputation he ruined by persuading Theodosius that she had an affair with Paulinus of Nola, master of offices (the equivalent of a Chief of Staff) and political rival of Chrysaphius. It should be noted, however, that Theodosius did not send his wife away in disgrace. She retained the title Augusta until her death and kept an imperial retinue, at least in the early years of her exile. She returned to Jerusalem, where she continued to contribute to the civic, social, and cultural scene there.

Christianity was gaining ground in the Eastern Empire around this time. Much of Eudocia’s poetry appears in the dedication of public works such as the baths of Hammat Gader. She was skilled in the art of the cento, a common practice of the literate classes of taking lines and allusions from classical Greek works such as the Iliad and the Odyssey and using those to write distinct and separate works to be read and recited at gatherings. She used this technique to paraphrase the Bible, taking a Hellenic poetic tradition to spread a growing religion.

Her poetry deserves mention here because her works contain the bending of social roles for some of her characters, among these Biblical ones. For example, in the story of Jesus and the Samaritan woman, Eudocia reworks Jesus’ reference to the gift of God from an allusion about living water into an allusion about nuptial gifts and a dowry. The characters become a spiritual bridal party, and Eudocia reverses and bends their gender identities. When the woman initiates gift-giving through the promise of civic generosity, food, drink, and gifts, she is being a good host. When she continues to bless the “man” who would lead Jesus into marriage and weigh him down with a dowry, this situates Jesus as a bride in search of a groom. The depiction of Jesus as a maternal woman is a theological explanation about Jesus’ own complex identities, including God, human being, and Sophia, a feminine personification. By describing Jesus as a guest laden with wedding gifts, Eudocia conflates Christian imagery of the Savior of the world with the classical Greek trope of a god disguised as a human being who is hosted by unwitting people.

Another of Eudocia’s works is a poetic reworking of a Christian prose narrative titled The Martyrdom of Cyprian, the story of a fictional Christian bishop and martyr. A central character in this story is a woman named Justina. Justina converts to Christianity in this poem, but during the narrative, she fights off the unwanted advances of one Aglaidas. She throws Aglaidas to the ground, scratches his cheeks, pulls out his hair and beard, and tears his clothes. She disfigures him and strips him of his clothing, a scene where a potential rape victim gives her assailant a taste of his own medicine. She also engages in battles with demons before becoming a deaconess in Antioch’s community. She eventually settles into a more traditional role, the superintendence and teaching of a community of early nuns, but her stint as a heroine of exceptional strength given to her through prayers and devotions must have given some young female readers moments of fierce satisfaction.

Source:

- Sowers, Brian P. In Her Own Words: The Life and Poetry of Aelia Eudocia. Harvard University Press, 2020.

~ M. Ana de Guzman, OL

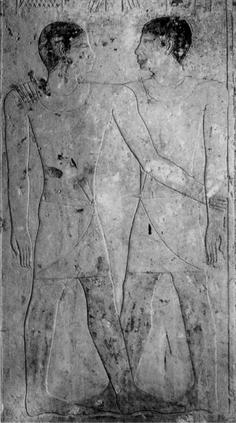

June 22- Khnumhotep & Niankhkhnum

Recorded as the first same-sex couple in the 5th dynasty of Egypt (approximately 2400 BC), the relationship between Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum has been debated since the uncovering of their shared tomb in 1964. While homosexuality as we know it is a rather modern concept, queer relationships are a part of our global history. Sexuality as a “dominant characterizing force” was not a defining trait in the ancient world. Preferences were acknowledged something akin to tastes in food and did not often serve as a basis for inequality or discrimination. For example, a rather ‘persistent rumor’ among scholars of Nubia states that of the 25th Dynasty of Egypt, aka the Kushite Empire around 744 BC to 656 BC, there were “entirely homosexual groups of men living in the kingdom of Kush.”

According to the surrounding hieroglyphs in their tomb, Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum shared the title of Overseer of the Manicurists in the Palace of the sixth pharaoh, King Nyuserre Ini. The two were depicted in intimate poses typically reserved for married couples such as standing or sitting together, holding hands, standing nose-to-nose, or embracing.

Archaeologists initially suggested that the two were ‘close friends’ to explain their ‘exaggerated affection’ (that they were twins was a later theory.) However, a banquet scene within their tomb showed space behind Niankhkhnum for his wife, eldest son, and his wife (with them being removed after being placed there) with Khnumhotep depicted on the other side with no space for family. He is, however, shown holding a lotus which, in the era of the Old Kingdom, was customarily saved for women. While there isn’t enough information or evidence to confirm whether Khnumhotep identified with womanhood himself, the fact that he’d solely taken the physical position of ‘wife’ when depicted alongside Niankhkhnum despite his own wife being present (albeit smaller and also smelling a lotus) is evidence that should be taken into consideration.

Although the label in which to place upon their relationship is still hotly debated, what archeologists cannot deny is the intimacy and closeness Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep had in life; so much so that their families respected their wishes to have them buried together with their epigraph reading ‘Joined in life and joined in death’.

Sources:

- Darling, L. (2016, December 20). Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum & Occam’s Razor. Making Queer History. https://www.makingqueerhistory.com/articles/2016/12/20/khnumhotep-and-niankhkhnum-and-occams-razor

- Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum aka Overseers of the Manicurists. (n.d.). Legacy Project Chicago. https://legacyprojectchicago.org/person/khnumhotep-and-niankhkhnum-aka-overseers-manicurists

- Parkinson, R. B. (1995). “Homosexual” Desire and Middle Kingdom Literature. The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology, 81(57). JSTOR. doi:10.2307/3821808

- Reeder, G. (2000). Same-sex desire, conjugal constructs, and the tomb of Niankhkhnum and Khnumhotep. World Archaeology, 32(2), 193-208. JSTOR. doi:10.1080/00438240050131180

- Ryan, H. (2018, February 22). Ancient Egypt Was Totally Queer. Them. https://www.them.us/story/themstory-ancient-egypt

- Wilford, J. N. (2005, December 20). A Mystery, Locked in Timeless Embrace. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2005/12/20/science/a-mystery-locked-in-timeless-embrace.htm

~Lady Sága Björnsdóttir (she/they)

June 21- Katherina Hetzeldorfer

When surveying lists of people tried and punished for homosexual activities in late medieval and early modern history, the collection leans very heavily toward men. There are several possibilities for this, including the fact that men’s lives, in general, were better recorded at this point in time; in particular, men were more likely to appear in court documents, a robust source of material about homosexual persecution.

Enter Katerina Hetzeldorfer, who is believed to be the first woman to be executed for homosexual activities.

Hetzeldorfer hailed from Nuremberg, Germany, but moved to Speyer in 1475, where she dressed in public as a man and lived with a woman who is variably referred to as either her sister or her wife. She was arrested and brought to trial, which is where things really get interesting. According to court testimony, Hetzeldorfer solicited sex from women, offering them what would be considered significant sums of money for their attentions; the lovers in question are recorded by the court scribe to praise the manly virility of the defendant and swearing that they believed Hetzeldorfer to be a man (Puff 45.) Court documents also accused Hetzeldorfer of “deflowering” her live-in lover and go so far as to include details about the construction of her dildo: “She made an instrument with a red piece of leather, at the front filled with cotton, and a wooden stick stuck into it, and made a hole through the wooden stick, put a string through, and tied it round” (Crawford 162). Hetzeldorfer was ultimately found guilty and drowned in the river Rhine in 1477.

But what was she found guilty of, exactly? As fascinating as the very specific testimony about Hetzeldorfer’s prowess as a lover and preferred sex toy is to read, an additional piece of intrigue here is the fact that no crime was specifically named. Given the extreme level of detail of the trial proceedings, a lack of something as seemingly straightforward as what she was charged with should be a significant oversight. In reality, this was not uncommon in Germany in the 15th century. There was growing concern in Speyer about cross-dressing during this period, where “the magistrate prohibited women from wearing men’s clothes, and later, men from wearing women’s clothes” (Puff 50) so Hetzeldorfer may have found herself a victim of this crime, though execution would be beyond the normal punishment for such an infraction. One theory presented by Puff is that the law lacked specific verbiage for lesbian sexual activities and would be simply considered “heresy.” If that theory holds, there are likely other women recorded as heretics who might today be more appropriately identified as queer.

Sources:

- Crawford, Katherine. European Sexualities, 1400-1800. Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- “Katherina Hetzeldorfer.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Katherina_Hetzeldorfer

- Puff, Helmut. “Female Sodomy: The Trial of Katherina Hetzeldorfer (1477).” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, vol. 30, no. 1, 2000, pp. 41-61.

~Maistresse Mariette de Bretagne, OP (she/her)

June 20- Walter Hungerford

We have all heard about King Henry VIII and how poorly he treated his wives. However, it was not only his wives that he treated poorly. Indeed, King Henry VIII was one of the first to bring sexual activities condemned by religion into secular criminal law by passing the Buggery Act of 1533. Aside from assisting the process of the dissolution of the monasteries and the seizing of their land and property to benefit the crown, the act, formally titled “An Acte for the punysshement of the vice of Buggerie,” made certain homosexual activities punishable by death in England.

Sir Walter Hungerford (1503–1540) was the first person to be executed under this act. Even though Sir Walter had been married three times and fathered children, he was not known for his kindness towards his third wife and accusations of homosexual activity were alleged. Arrested in 1540, Sir Walter was accused of being “Replete with innumerable, detestable and abominable vices and wretchedness of living… and hath accustomably exercised, frequented, and used the abominable and detestable vice and sin of buggery with William Master, Thomas Smith and other of his servants.”

Due to his relationship with Thomas Cromwell and quick rise in favor, as well as his not-so-subtle support of the Pilgrimage of Grace revolt, it is more probable that treason is what cost him his head. Be that as it may, Sir Walter was the ONLY person executed under this act in the Tudor period. The act was repealed by Queen Mary (shocking!) after her father’s death but reinstituted by her sister, Queen Elizabeth, upon her succession. It has been suggested that this charge was tacked on to the others to humiliate him and add more weight to the case against him.

It wasn’t until July 27, 1967, when England passed the Sexual Offenses Act, that private homosexual acts between two men, both over the age of 21, were finally decriminalized. This was the start of a revolution for sexual freedoms that has lasted over 50 years in England, though the fight for equality there and in other areas of the Commonwealth remains ongoing.

Sources:

- “Buggery Act 1533.” UK LGTB Archive, https://lgbthistoryuk.org/wiki/Buggery_Act_1533

- “Walter Hungerford.” UK LGTB Archive, https://lgbthistoryuk.org/wiki/Walter_Hungerford?fbclid=IwAR3AHOOLk9IMP4fcHICYw2FZf5luftctr42LQ_WfqQIDiXzOg6bVLqjX0nA

- “Walter Hungerford and the Buggery Act.” English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/learn/histories/lgbtq-history/walter-hungerford-and-the-buggery-act/

- “A Timeline of LGTB Communities in the UK.” British Library, https://www.bl.uk/LGBTQ-histories/lgbtq-timeline#Sexual%20Offences%20Act

~Viscountess Sefa Hrafnsdóttir, OP (she/her)

June 18- The Hijras

In Sanskrit, the word trityaprikruti identifies the genders of Hindu people. By today’s definition, we would consider these three distinct genders: male, female, and a gender-neutral group called the Hijras. The Hijras have been considered blessed, recognized as a third gender, and worked as eunuchs, proof of non-binary gender existence throughout India’s long history.

One of the first literary references to the Hijras was in the Ramayana, a 2000-year-old epic poem by Valmiki. The poem tells the story of Lord Rama, a Hindu god-king, being exiled to the forest with his people. He tells all the women and men to leave, but a group is remained, since they were neither men nor women. These people, the Hijras, he tells to wait in the forest for his return. They remained in the woods for 14 years for Lord Rama’s to reappear. For their patience, the Hijras become his Blessed.

Throughout the history of Hinduism, the Hijras brought blessing to birth rituals and weddings. During the time of the Mughal Empire, the Hijras were also the eunuch guards of the Emperor’s Harem.

Today, the Hijras are considered transgender or intersex people. They can be found begging on the street near train stations or providing sex work; “they sashay through crowded intersections knocking on car windows with the edge of a coin and offering blessings. They dance at temples. They crash fancy weddings and birth ceremonies, singing bawdy songs and leaving with fistfuls of rupees. Many Indians believe hijras have the power to bless or curse, and hijras trade off this uneasy ambivalence” (Gettleman).

In the past, traditional Hindu culture allowed hijras to live in Indian society with a “certain degree of respect.” The British colonization of India during the 19th century altered their already tenuous position, as the Victorian’s particularly limited viewpoint did not permit for such nuances of sex and gender, with the British criminalizing “carnal intercourse against the order of nature,” and according to Gettleman, this was the beginning “of a mainstream discomfort in India with homosexuality, transgender people and hijras.”

Sources:

- Menon, Ramesh. Ramayama: A Modern Retelling of the Great Indian Epic. North Point Press, 2004.

- Gettleman, Jeff. “The Peculiar Position of India’s Third Gender.” New York Times, 17 Feb. 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/17/style/india-third-gender-hijras-transgender.html

~kasumi no tanaka, OP (she/her)

June 17- Albrecht Dürer

Albrecht Dürer is regarded as an archetype of Renaissance artists in Northern Europe. He was a writer, a theoretician, and an engraver, but was most famously known as a painter and woodworker. Born in 1471 in Nuremberg as one of eighteen children 9though only 3 survived to adulthood), he spent years honing his skills traveling to and from Venice. During one such trip in 1494, a marriage was arranged for him, by his parents, to Agnes Frey. Though they remained married for the rest of his life, they never had children. According to letters sent between Dürer and his friends, his relationship with Agnes was one based on financial gain. In one letter between Willibald Pirckheimer to Johan Tscherte, Pirckheimer states that he blames Frey for Dürer’s death after “she drove him to work hard day and night solely in order to earn money that he would leave to her when he died because she wanted to ruin everything…”

Dürer’s artistic break came in 1496 when he was commissioned to paint a portrait of the Elector of Saxony, Frederick the Wise. After said commission, he was brought on to paint the palace chapel in Wittenburg. Though his portraits and paintings were gaining popularity, his wood carvings were the main source of his rising fame. One of his first published works was a depiction of the Biblical book of Revelations, in a piece titled “Apocalypse with Pictures” in which Dürer created a series of fifteen relief style wood engravings.

It is often said that Dürer was bisexual, evidenced by the homoerotic visuals and the “theme of Homosexual behavior” that are quite prevalent in his works. After his wood carving art gained popularity, he began to branch from the religious works and stylings of Venice to develop his own style, richly influenced by Roman sacred stories and other artists such as Mantega, Leonardo, and Geovani Bellini. Two such works that give weight to the belief of his same-sex attractions are Dürer’s wood carvings depicting Hercules and Orpheus, two characters who are often interpreted to have homosexual tendencies in their mythos stories, particularly Orpheus, whose carving depicts a banner stating “Orpheus, The First Sodomite.” As his art progressed, his lovers began to appear as figures in his works, The Bath House depicts his attraction to his lovers, as it shows four men and two musicians naked in a bath house in Nuremberg. The men are Stephen Paumgarther, Lucas Paumgarther, Willibald Pirckheimer, and Dürer himself. In the work, the phallic fountain covers the genitals of Dürer’s character while he looks at his lovers. The men make another appearance in the Paumgartner altarpiece.

In Dürer’s letters to Pirckheimer, the men allude to homosexual activity on the part of the other. It is theorized that Pirckheimer was Dürer’s most intimate lover, heavily reinforced given that in one portrait of Pirckheimer, written on the page in Greek is a phrase that roughly translates to “with a cock in his asshole.” However, though the homosexual visuals in his work are prominent, in his letters it is clear that Dürer was interested in both sexes. Pirckheimer wrote that “whores and pious women” alike were asking about the whereabouts of Dürer while he was in Venice in 1506.

Dürer dedicated his life to developing the understanding of art. In 1504, he stated the idea that artistic value was detached from manual skill. He published two books in his lifetime and one after his death; in total, there are over 1,300 works in Dürer’s collection. Dürer’s work shows us his muses and that even if you aren’t openly out in the community, you can still show them off to the world (and also that arranged marriages aren’t for everyone.)

Sources:

- “Albrecht Dürer: Excerpts from Primary Documents.” http://employees.oneonta.edu/farberas/arth/arth200/artist/Dürer_primary_docs.html.

- “The Complete Works – Biography.” Albrecht Dürer, 2017, https://www.albrecht-Dürer.org/biography.html

- Dürer, Albrecht. “Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1528).” National Gallery, https://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/artists/albrecht-Dürer.

- Garner, Elizabeth. “Crimes in the Art: The Secret Cipher of Albrecht Dürer.” The Hidden Secrets in Albrecht Dürer’s Art and Life, 17 Sept 2012, http://www.albrechtDürerblog.com/sex-in-the-nuremberg-bathhouse/.

- Hoke, Casey. “Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528).” Queer Art History, 25 July 2017, https://www.queerarthistory.com/uncategorized/albrecht-Dürer-1471-1528/.

- Ruhmer, Eberhard. “Albrecht Dürer | Biography, Prints, Paintings, Woodcuts, Adam and Eve, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 17 May 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Albrecht-Dürer-German-artist#ref1948.

- Wood, Christopher. “This Strange Speech: Early Dürer.” London Review of Books, 18 July 2013, https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v35/n14/christopher-s.-wood/this-strange-speech.

June 16- Ergi

When people use the word ‘Viking,’ especially outside of the SCA, they probably picture a large person with matted hair, tattoos, muscles enlarged from battle, something most people would consider to be the epitome of masculinity, right? Now, what if I told you this picture in your head is only a half truth? What if someone told you that queer Vikings (even Gods!) existed?

From all the stories we have heard and research many of us have done, we know that the Viking world was massive and wide-ranging. Across a few hundred years and spanning people in Scandinavia (modern day Norway, Denmark, and Sweden) as well as the migration to Iceland, the north of England, Ireland, Normandy, the Volga River, and plenty other places, it is unlikely for a culture that far-reaching to have existed without queer people.

The Viking world had a word in Old Norse that makes it very easy to look for queerness: ergi. This word’s meaning is still debated but seems to have the overarching meaning of “doing gender wrong,” while some more specific meanings include “unmanliness” and “female lust.” Amy Jefford Franks translates ergi to be “queer” because that ultimately seems to be the meaning. A few documented examples of queer Vikings in the historical record may help to explore the range of this word.

First, Odin himself, the god of war, poetry, and death, is referenced as ergi a number of times in Norse mythology. In the story Lokasenna (The Flyting of Loki) in the Poetic Edda, Aegir was hosting a feast for the gods. Offended that he wasn’t invited, Loki storms in and starts insulting the gods one by one. At one point, Loki turns to Odin and says:

“And you practiced magic,

In Samsey,

And you struck on a drum like a sorceress;

In a wizard’s form you travelled over mankind,

And I thought that was ergi [queer] in nature.”

Additionally, in the poem The Lay of Hárbarðr, also from the Poetic Edda, Odin is disguised as a ferryman called Hárbarðr and is refusing to help Thor cross the river. Eventually, Thor shouts “Hárbarðr you queer” as an insult. This seems to be in reference to Odin earlier bragging about practicing a specific form of magic known in Old Norse as seiðr. By practicing magic, Odin is portraying himself as a woman as it was only women that could practice this form of magic.

Modern understandings of queerness also helps us to explore how identities could have looked in the past. Indeed, queer people have always existed. However, the way that queerness looked is not fixed. One example to look at is burial Bj. 518. This burial was found in the Viking Age site of Birka, on the island of Björkö in Sweden. When first excavated, the burial site was immediately presumed to be that of a male warrior. They had been sent to Valhalla with a complete set of weapons, two horses, and a full set of gaming pieces. In 2017, it was found that the person was actually female. The researchers who made this discovery announced that therefore this was the first confirmed high-ranking Viking warrior woman. There were no items in this burial site to suggest that this individual took on a feminine role (like other gravesites with beads, drop spindles, or other feminine associated items). Instead, it may be that by becoming a warrior, they also became a man, and were understood to be a man by their community. It is possible that this individual is what we would understand now to be a transgender man.

The Viking world was vast. The way that queerness shows up again and again mythological and physical worlds, it is easy to see how the queer community has always been here.

Sources:

- “Hárbarðsljóð.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H%C3%A1rbar%C3%B0slj%C3%B3%C3%B0#:~:text=H%C3%A1rbar%C3%B0slj%C3%B3%C3%B0%20(Old%20Norse%3A%20’The,history%20as%20an%20oral%20poem

- Hedenstierna-Jonson, Charlotte. “Grave Bj 581: The Viking Warrior That Was a Woman.” https://www.medievalists.net/2019/12/grave-bj-581-the-viking-warrior-that-was-a-woman/

- Jefford Franks, Amy. “Approaching Queerness In The Viking World.” http://www.historymatters.group.shef.ac.uk/queerness-viking-world/?fbclid=IwAR3an5CNQgoh8EEKUNJ4HnxsF_2GMneugYvf8Bg7E16H8AF8-fdZpnQRR_o

- “Lokasenna.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lokasenna

~Viscountess Sefa Hrafnsdóttir, OP (she/her)

June 15- Persecution as Proof

At the halfway point of this Pride month project, we have already seen stories of the queer experience spanning the globe across over 2,000 years of history. Given that, it can be truly frustrating that there are people in the 21st century who aim to paint queerness as something new or modern. Sometimes people try to argue that the increased number of individuals publicly acknowledging their queer identity is a result of whatever perceived societal ill is in their crosshairs, blaming everything from shows like Queer Eye on television to mothers not staying at home with their children to instances of child abuse (a myth debunked by the Southern Poverty Law Center.) In reality, modern science has supported the idea that a person’s sexual orientation is not a choice influenced by what you watch on TV, but rather a combination of biological and environmental factors.

In period, however, a time before queer visibility on television, latchkey kids, or a complete understanding of genetics, we have plenty of evidence that queer people existed in large enough numbers to draw the attention of lawmakers both temporal and ecclesiastical, inspiring them to create gruesome punishments to discourage and punish queer behavior. Flogging, exile, mutilation, burning, being buried alive: these are just some of the techniques used to punish queer people in the Middle Ages. The list of every document or office prescribing punishment for queer behavior would be a textbook unto itself, but a brief collection of some of them include:

- The Council of Nablus (Kingdom of Jerusalem, 1120)

- Livres de Jostice et de Plet (Orléans region of France, c. 1260)

- The Office of the Night (Florence, 15th century)

- The Buggery Act (England, 1533)

For anyone attempting to deny the existence of queer people in the Middle Ages, one must ask the question: if queer people weren’t there, why would they need so many laws to punish their existence?

Before we get too comfortable about the century we’re living in, it might be good to remember that homosexuality was still classified as a mental illness by the American Psychiatric Association until 1973 (and by the World Health Organization until 1981.) The American Bar Association only supported decriminalization of consensual adult homosexual acts in 1974. Perhaps no one is suggesting legislation promoting castration for having consensual sex with your partners in the United States in 2022, but there are still almost 70 countries in the world where it is illegal to be gay.

We will continue highlighting queer figures for the rest of Pride, sharing figures both celebratory and tragic, but at the halfway point, we hope it is already abundantly clear: queer is period.

~Maistresse Mariette de Bretagne, OP (she/her)

June 13- Rumi

Rumi was a 13th-century Persian poet and Sufi mystic whose love for another man inspired some of the world’s best poetry and led to the creation of a new sect of Islamic Sufism, the Mevlevi Order, better known as the Whirling Dervishes. With sensuous beauty and magnificent spiritual insight, Rumi writes about the sacred presence in the ordinary, everyday experiences of life. He once wrote, “love is the bridge between you and everything,” which illustrates why his poetry has been admired around the world for centuries and how he continues to be one of the most popular poets in America. One of his oft-quoted poems begins:

“If anyone asks you

how the perfect satisfaction,

of all our sexual wanting

will look, lift your face

and say,

Like this.”

Given this, it is no prejudication that the homoeroticism of Rumi is hidden in plain sight. It is well known that his poems were inspired by his love for another man, but the queer implications are scarcely discussed. There is no proof that Rumi and his beloved Shams of Tabriz had a sexual relationship, but the intensity of their same-sex love is undeniable.

Rumi’s life changed when he met a man called Shams. Rumi’s father died when Rumi was young, and he inherited a position as teacher at a madrassa (Islamic school). He continued studying Islamic law, eventually issuing his own fatwas (legal opinions) and gained favor and notoriety by giving sermons at local mosques. Rumi also practiced the basics of Sufi mysticism in a community of dervishes, despite this behavior and belief system being generally looked down upon by other sects of Islam. Then Shams of Tabriz arrived. It is said that Shams had traveled throughout the Middle East asking Allah to help him find a friend who could “endure” his companionship. A voice in a vision sent him to the place where Rumi lived (Cherry, 2022). The initial spark of their connection inspired Rumi to take Shams into his home, and the two become inseparable. Many theories surround Shams’ eventual disappearance from Rumi’s life. Popular theory suggests Rumi’s youngest son, who had a special closeness to Shams’ wife Kimia, committed an honor killing on Shams for causing her death. Other tales claim Rumi’s disciples murdered Shams out of jealousy. Or perhaps, in true Sufi fashion, Shams left Rumi, in the dead of night, and became the wanderer he always was. Regardless of the reason for the absence, after Rumi waited for 40 days with no news of Shams, he donned a black robe from then on and proclaimed Shams dead (Shiva, 2018).

Undoubtedly, Rumi developed an intense relationship Shams, but knowing to what extent that relationship reached is a challenge to ascertain. What is indisputable is that Shams embodied Rumi’s idea of the ‘Perfect Human being’ in the tradition of Ibn Arabi. The love expressed for Shams is love for all that a human could be (Mir, 2020). Furthermore, what has been documented is that Rumi couldn’t bear the painful separation from his Sheik and poured his emotions through poetry, writing tens of thousands of verses. It is estimated that Rumi wrote over 3,000 poems for Shams, expressing his love and devotion for his guide who he referred to as the bird and the sun who showed him the right path (Pareek, 2017). And while contemporary terms of gay, homosexual, and queer cannot cleanly be imposed upon writing and figures from centuries ago, it also cannot be doubted that Rumi and Shams had a some type of intense affair. Rumi and Shams were inseparable, both emotionally and physically. They spent months together, lost in a kind of ecstatic mystical communion known as “sobhet”, conversing and gazing at each other until a deeper conversation occurred without words (Cherry, 2022). Rumi danced, mourned, and wrote poems until the pressure forged a new consciousness, uttering, “the wound is the place where the Light enters you”. In the end, his soul fused with his beloved. They became One: Rumi, Shams, and God, blended together in ecstasy. Or in Rumi’s words:

There is some kiss we want

with our whole lives,

the touch of Spirit on the body.

Seawater begs the pearl

to break its shell.

And the lily, how passionately

it needs some wild Darling!

At night, I open the window

and ask the moon to come

and press its face into mine.

Breathe into me.

Close the language-door,

and open the love-window.

The moon won’t use the door,

only the window.

Sources:

- Cherry, Kittredge (2022). “Rumi: Poet and Sufi mystic inspired by same-sex love.” https://qspirit.net/rumi-same-sex-love/

- Mir, Foad. (2020.) “Rumi and his Muse, Shams.” https://medium.com/@foadmir2/rumi-and-his-muse-shams-514c6940751

- Pareek, Shabdita. (2017). “Here’s The Man Who Inspired Rumi’s Writings & Made Him The Celebrated Poet We Know Today.” https://www.scoopwhoop.com/Shams-Tabrizi-The-Man-Who-Mentored-Rumi/

- Shiva, Shahram. “Rumi’s Untold Story.” https://www.rumi.net/about_rumi_main.htm

~Lady Aisha bint Allan (she/they)

June 12- Māhū

Polynesian culture, more specifically Hawaiian culture, is rich in oral tradition, expressed through stories (Moʻolelo), songs (Mele), or dance (Hula). Many people may not realize that some of the most revered and respected practitioners of all of these are Māhū, meaning “in the Middle” in Native Hawaiian and Tahitian culture, or the third gender. They were looked to for their insight, wisdom, and knowledge.

According to present-day māhū kumu (teacher) hula Kaua’i Iki, “Māhū were particularly respected as teachers, usually of hula dance and chant. In pre-contact times māhū performed the roles of goddesses in hula dances that took place in temples that were off-limits to women. Māhū were also valued as the keepers of cultural traditions, such as the passing down of genealogies. Traditionally parents would ask māhū to name their children.”

One of the earliest and most well-known Mo’oelo is the “He moolelo kekahi no ka pohaku kahuna Kapaemahu” (The story of the Kapaemahu priest stones). It is said before the time of the great chief Kakuhihewa of Oʻahu four soothsayers or wizards came from the land of Moaulanuiakea (Tahiti). They were named Kapaemahu, who was the leader, Kinohi, Kahaloa and Kapuni. They traveled around the island of O’ahu, were described as unsexed by nature, and their habits coincided with their feminine appearance although manly in stature and bearing courteous ways, kindly manners, and “low, soft speech.” They were Māhū – a Polynesian term for third gender individuals who are neither male nor female but a mixture of both in mind, heart, and spirit.

They eventually settled in Waikiki, specifically Ulukou on O’ahu. There they performed with their skill in the science of healing. They affected many cures by the “laying on of hands,” and became famous across the island. When it was time for the Māhū to leave the island, those who witnessed or were actually cured by them decided to erect a monument to the great teachers and healers. From the hills of Kaimuki three miles away, four boulders were brought to Waikiki. Two were placed in the ocean where the Māhū bathed and two were in the ground close to their dwelling.

It is then said that the Kapaemahu began a series of ceremonies and chants to embed the healers’ powers within the stones, burying idols indicating the dual male and female spirit of the healers under each one. The legend also states that “sacrifice was offered of a lovely, virtuous chiefess,” and that the “incantations, prayers and fasting lasted one full moon.” Once their spiritual powers had been transferred to the stones, the four Māhū vanished and were never seen again.

Over many centuries the stones stayed and were eventually removed, moved, and buried under a bowling alley. It wasn’t until intervention by kanaka (indigenous Hawaiians) and the government got the stones were restored and enhanced in security and viewing in 1997. They stand today in Waikiki not far from the Statues of Duke Kahanamoku and King David Kalākaua. The Mahu were and now are accepted in Hawai‘i as it was throughout Polynesia, defined in part by what it was not: a demographic, a race, an excluded minority, contrary to what Christian missionaries spent decades claiming. Polynesian and Hawaiian cultures accepted and even held sacred the third gendered, the Māhū.

If you would like to see a wonderful animation of the story of Kapaemahu, follow this link to a short video from PBS: https://www.pbs.org/video/kapaemahu-lylrwy/

Sources:

- Kaua’i Iki, quoted by Andrew Matzner in “’Transgender, queens, mahu, whatever’: An Oral History from Hawai’i.” Intersections: Gender, History and Culture in the Asian Context, Issue 6, August 2001.

- “Ka Buke Almanaka a Thrum.” Ka Nupepa Kuokoa, 1907, Jan 4, p. 1.

- “The Wizard Stones of Ka-Pae-Mahu.” 2001. More Hawaiian Folk Tales: A Collection of Native Legends and Traditions. University Press of the Pacific.

- Dvorak, Greg, Delihna Ehmes, Evile Feleti, Tēvita ʻŌ. Kaʻili, Teresia Teaiwa, and James Perez Viernes. 2018. “Gender in the Pacific.” Teaching Oceania Series, edited by Monica C. LaBriola. Center for Pacific Islands Studies, University of Hawaii–Manoa.

- “Wizard Stones’ Blessed.” Honolulu Advertiser, 1997, Mar. 4, p. 1.

- Pagliaro, Emily. 1997. Nā Pōhaku Ola Kapaemāhū a Kapuni Restoration. Fields Masonry, Hawaii, Queen Emma Foundation Historic Preservation Division, Honolulu, Hawai’i.

~Lord Albrecht Anker (he/him)

June 11- Agnolo Bronzino

Sometimes, a poem about cheese may not actually be talking about cheese.

Such is the double entendre of the worlds walked by Agnolo di Cosimo, famously known as Agnolo Bronzino (1503 – 1572), the Italian painter lauded for his paintings and drawings that swept the courts of Duke Cosimo de Medici and Duchess Eleonora di Toledo in 16th Century Italy.

Bronzino’s connections to his peers and loved ones were complex and nuanced. He painted men who were known to have patron and romantic connections, such as Luca Martini and Piero da Vinci. Bronzino was also known to participate in burlesque poetry inside and outside Academy circles, a genre of writing full of double meanings and codes meant for those who knew the “true” and often risqué meanings of the prose. Bronzino’s own poems “Il Raviggiuolo” and “Della Cipolla del Bronzino, Pittore” would make the most indecorous person you know blush and laugh at the same time.

While Bronzino’s lifestyle as a painter and hobby-poet could brand him as “Queer” in the 21st Century, the comings and goings of Bronzino were largely left unsaid outside of letters and mentions of his “relations” to others, due to the attitudes of male friendship and sexuality of the period. As mentioned by Lisa Kaborycha’s lecture “Among Rare Men: Bronzino and Homoerotic Culture at the Medici Court,” sodomy laws, shifting demographics, and the pressing authoritative application of Duke Cosimo’s hand for decades affected the lives of artists and “Queers” such as Bronzino. The levels of discretion he partook during his life leaves us a blurry and unpolished picture of Bronzino’s identity, much like the scratched fresco left behind by his student.

For Pride month we celebrate not just the brusque and the camp in our lives, but the ability to live the best we can in the time that we are given; for while Dukes may come and go, and laws may pass and repeal, art is persistent and everlasting.

Source:

- Kaborycha, Lisa. “Among Rare Men: Bronzino and Homoerotic Culture at the Medici Court.” 5 April 2010, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJdaupuUzUw

~Cateline Straquhin, Armiger (she/they)

June 10- Jeanne d’Arc

Born around 1412, Jeanne d’Arc (translated in English to Joan of Arc) was the daughter of a tenant farmer from the village of Domrémy, in northeastern France. A peasant girl, Joan of Arc could neither read nor write, but firmly believed that God had chosen her to lead France to victory in its long-running war with England. Despite a lack of military training, Joan convinced the embattled crown prince Charles of Valois to allow her to lead a French army to the besieged city of Orléans, achieving a momentous victory over the English and the Burgundians. After seeing King Charles VII crowned, Joan was captured by Anglo-Burgundian forces, tried for witchcraft and heresy, and burned at the stake in 1431, at the age of 19. The Burgundians referred to her as hommasse, a slur meaning “manwoman,” or masculine woman (Feinberg, 1996). By the time she was canonized by the Catholic Church in 1920, the “Maid of Orléans” had long been considered one of history’s greatest saints, and an enduring symbol of French unity and nationalism.

While Joan’s prowess in battle and Godly devotion cannot be ignored, what is often overlooked is Joan of Arc was a cross-dressing teenage warrior who led her army to victory when she was just 17. In May of 1428, Joan had made her way to the stronghold of Charles followers in Vaucouleurs. Despite initially being rejected by the local magistrate, Robert de Baudricourt, she persisted, and attracted a small band of followers who believed her claims to be the virgin of prophecy destined to save France. When Baudricort relented, Joan cropped her hair and dressed in men’s clothes to make the journey across enemy territory to the site of the crown prince’s palace (History.com, 2022). Queer writers tend to downplay Joan’s Christian faith, while the Church covers up the importance of her cross-dressing. According to the historical records and writing of the time, one can assume that Joan believed strongly in God AND in cross-dressing. She insisted that God wanted her to wear men’s clothes, making her what today can be called “queer,” “lesbian” or “transgender” (Cherry, 2022). Though it’s hard to apply these contemporary categories to people who lived centuries before those terms existed, both the lesbian and trans communities claim Joan as one of their own.

Nobody knows for sure whether Joan of Arc was sexually attracted to women or had lesbian encounters, but her abstinence from sex with men is well documented. Her physical virginity was confirmed by official examinations at least twice during her lifetime. Joan herself liked to be called La Pucelle, French for “the Maid,” a nickname that emphasized her virginity (Cherry, 2022). Witnesses at her trial testified that Joan was chaste rather than sexually active. Contemporary feminists believe that when the term “virgin” was used, it didn’t mean sexless, but rather belonging to no man. There are many “virgin saints” who refused heterosexual marriage and joined convents to have their primary relationships with women. These figures are often revered as role models for lesbians and queer persons of faith.

One of the first modern writers to raise issues of gender identity and sexuality was early 20th century novelist Vita Sackville-West. In Saint Joan of Arc, published in 1936, she suggests that Joan of Arc may have been a lesbian due to sharing a bed with women (Sackville-West, 1936). Warner also argues that in pre-industrial Europe, a link existed between cross-dressing and priestly functions, hence justifying the historical interpretation of her as both a witch and a saint (Sackville-West, 1936). Warner further argues for Joan as not occupying either a male or female gender: “Through her [cross-dressing], she abrogated the destiny of womankind. She could thereby transcend her sex… At the same time, by never pretending to be other than a woman and a maid, she was usurping a man’s function but shaking off the trammels of his sex altogether to occupy a different, third order, neither male nor female” (Sackville-West, 1936). Warner categorizes Joan as an androgyne. Even though she knew her defiance meant she was considered damned, Joan’s testimony in her own defense revealed how deeply her cross-dressing was rooted in her identity. ‘”For nothing in the world,” she declared, “will I swear not to arm myself and put on a man’s dress”’ (Feinberg, 1996). Regardless of modern queer terminology labeling Joan of Arc as lesbian, transgender, nonbinary or androgynous, what is irreputable the strength and symbolism that she continues to be for modern day Queers. In the contemporary, Joan is recognized as a kindred spirit and role model in her stubborn defiance of gender rules.

Sources:

- Cherry, Kittredge (2022). “Joan of Arc: Cross-dressing warrior-saint and LGBTQ role model.” https://qspirit.net/joan-of-arc-cross-dressing-lgbtq/

- Feinberg, Leslie (1996). Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to Dennis Rodman. Beacon Press.

- “Joan of Arc” (2020). https://www.history.com/topics/middle-ages/saint-joan-of-arc

- Sackville-West, Vita (1936). Saint Joan of Arc. Doubleday.

~Lady Aisha bint Allan (she/they)

June 9- Eleanor Rykener

In 1995 an article was published in GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies introducing to the historical record a newly discovered document that summarized the court testimony of Eleanor, a sex worker who was arrested in December of 1394, along with the man who had propositioned her. While both individuals gave testimony, Eleanor’s was longer and much more detailed, as she discussed her history in some depth, relating examples of her work as a prostitute, an embroiderer, and a tapster/barmaid, along with references to some of her other more personal sexual encounters.

While testimony from a sex worker would be interesting enough in a historical record otherwise filled with the stories of the social elite, what makes this document particularly important is the fact that Eleanor, also known during her life by the name John Rykner, was biologically male and dressed in women’s clothing at the time of her arrest.

The historians who wrote about her testimony over 25 years ago referred to Eleanor as a “transvestite prostitute,” used he/him pronouns, and focused their attention on this case as an example of male-to-male sexual relations, largely discussing it in the context of English laws related to sodomy. However, scholars working in the present day are more likely to argue for and support Eleanor’s identity as a transgender woman. While it is true that Eleanor’s fact-based account of her life does not include explicit comments about her personal feelings regarding her gender or sexual identity, there are several factors of her life and public presentation that align with our modern understanding of this identity.

During her court testimony, she asked to be called by the name of Eleanor, showing a strong preference for a female form of address. PhD candidate Kadin Henningsen asserts that “by making this statement [Eleanor] strategically…inscribes herself into the historical record as a woman.” Henningsen also argues that modern history should identify Eleanor as a transgender woman “because she lived and worked for periods of her life as a woman, and [because] other people in her social milieu accepted her as such.” During her testimony, Eleanor described residing with other women whom she noted taught her to dress, act, and have sex as a woman. By working as an embroiderer, Eleonore was engaged in a job that was predominantly seen as women’s work, and during this period in English history, women were as equally likely as men to work as tapsters serving alcohol in taverns. Finally, prostitution at this point in medieval society was almost exclusively associated with the female gender; there are no other court cases during this time where a man was accused or convicted of prostitution. Henningsen lays out this evidence and argues that, while we cannot assume “a ‘historical equivalency’ between trans women today and trans women in the past,” Eleanor, through her choice of a name, dress, and employment used “common understandings of femininity and womanhood of the period to mark herself as a woman.”

Sources:

- Kadin Henningsen, “Calling [herself] Eleanor”: Gender Labor and Becoming a Woman in the Rykner Case,” Medieval Feminist Forum: A Journal of Gender and Sexuality, 55(1), 2019, https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/mff/vol55/iss1/9/

- Samantha Charland, “Gender Fluidity in Medieval London: Considering the Transvestite Prostitute Eleanor John as Lesbian- Like Woman,” In Imagining the Self, Constructing the Past (edited by Sulivan and Pages), 44-52. Google Books.

- Ruth Karras, Sexuality in Medieval Europe: Doing Unto Others (second edition), Routledge, 2012

- “John/Eleanor Rykener,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John/Eleanor_Rykener

Note: It is also important to note that Eleanor may have been a bisexual or lesbian transgender woman. While she was paid to have sex with men, Eleanor noted in her court testimony that she also had sex with women at various times in her life but did not receive money in those instances. This may indicate that she had a preference for sexual encounters with women.

~Mistress Elysabeth Underhill (she/her)

June 8- Nzinga Mbande

Born in 1583 in present-day Angola, Nzinga Mbande was the Ngola (which translates to ‘ruler’) of Ndongo (1624-1663) and Matamba (1631-1663) until her death on December 17, 1663, at the age of eighty-one.

Legend says that her birth was a difficult one, as her umbilical cord was wrapped around her neck. Considering that those who survived ‘unusual births’ in the royal family were believed to have spiritual gifts or become a powerful person later in life, it is not surprising that she was her father’s favorite child and received extensive military training to fight alongside him in battle. Nzinga displayed an aptitude for warfare and preferred the traditional weapon of Ndongan warriors: the battle axe.

The interest in Nzinga as a queer person in history should also be extended to pre-colonial Ngola. Gender roles outside of Western standards (and even then) were and continue to be different. Historical reports from regions all over Africa show that gender does not coincide with biological sex.

As the throne of Ngola could only be held by men, Nzinga chose to dress in traditional kingly attire and was then regarded as a man which led to the need of a harem of wives to produce heirs (as kings were wont to do.) Olfert Dapper, a Dutch geographer, wrote in his 1668 account of Nzinga’s court, “(She) also maintains fifty to sixty concubines, whom she dresses like women, even though they are young men… Even though they know it, she dresses these fifty to sixty strong and beautiful young men in female garment, according to her habit, and dresses herself as a man. She calls these men women and herself a man…”

Ngola Nzinga is still regarded as a hero of Angola for pushing back against Portuguese slavers and colonial rule, and is an example of pre-colonial, African gender fluidity.

Sources:

- Burness, D. (1977). “Nzinga Mbandi” and Angolan Independence. Luso-Brazilian Review, 14(2), 225-229. doi:10.2307/3513061

- Carlson-Ghost, M. (2017, September 25). Queen Nzinga: An African “King” to be Reckoned With. Mark Carlson-Ghost: Celebrating diversity in culture, myth and history. https://www.markcarlson-ghost.com/index.php/2017/09/25/queen-nzinga-warrior-woman-king/

- Donnella, L. (2017, May 12). Picturing Queer Africans in The Diaspora: Code Switch. NPR. https://www.npr.org/sections/codeswitch/2017/05/12/476893927/picturing-queer-africans-in-the-diaspora

- Elliot, M., & Hughes, J. (2019, August 19). A Brief History of Slavery That You Didn’t Learn in School. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/19/magazine/history-slavery-smithsonian.html?mtrref=en.wikipedia.org&gwh=270F68346427E87C6F89CF85CC94B2D4&gwt=pay&assetType=PAYWALL

- Miller, J. C. (1975). Nzinga of Matamba in a new perspective. The Journal of African History, 16(2), 201-. doi:10.1017/S0021853700001122

- Terence. (2010, August 11). Nzinga (1583-1663), Female King of the Mbundu. Queers in History. http://queerhistory.blogspot.com/2010/08/nzinga-1583-1663-female-king-of-mbundu.html

- Zagria. (2013, September 11). Nzinga Mbandi (1583 – 1663) queen. A Gender Variance Who’s Who. https://zagria.blogspot.com/2013/09/nzinga-mbandi-1583-1663-queen.html#.YpwMf3bMKHv

~Lady Sága Björnsdóttir (she/they)

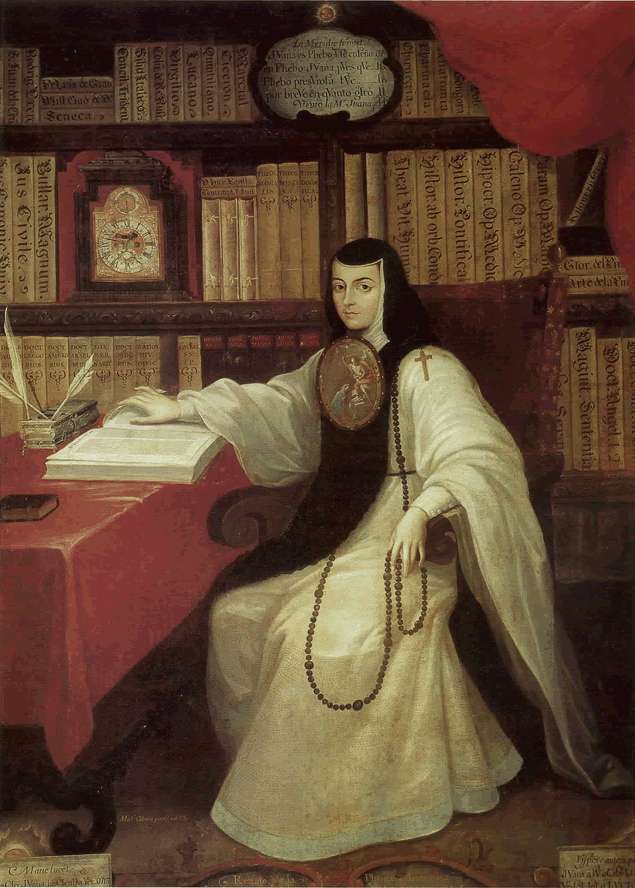

June 7- Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648-1695) was a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer, and poet. Her mental prowess and contributions to the Spanish Golden Age earned her the names “The Tenth Muse” and “The Phoenix of America.” Modern scholars have called her work proto-feminist, acknowledging her as a contributor to the Querelles des Femmes, an early feminist debate on the nature of women and campaign for social change. Sor Juana’s writings tackle the concepts of gender, education rights, women’s religious authority, and colonialism. Her work Respuesta a Sor Filotea is credited as the first feminist publication of the New World.

In her early years, Sor Juana had an avid love of learning. Although formal education was forbidden to girls, she taught herself to read and write Latin by the age of 3. By the age of 13 she was composing poetry, some of which was written in the Aztec language Nahuatl; she also had a solid mastery of Greek logic. When she was 16, she asked her mother if she could cut her hair and disguise herself as a boy in order to further her formal education and attend university. When this plan failed, she became a lady-in-waiting to the colonial viceroy’s court. It was here that she was taken under the wing of Vicereine Donna Eleonora del Carretto. Impressed with her intelligence, the viceroy invited numerous theologians, philosophers, jurists, and poets to meet with young Sor Juana to engage in academic discourse. Through these interviews, her word fame spread, and she received a number of marriage proposals, which she declined.

In 1667, she entered into monastic life and became a nun, giving her the freedom to continue her studies. During this time, she began writing poetry and prose on the topics of love, feminism, and religion. She amassed the largest library in the New World and turned her nun’s quarters into a salon where she was frequently visited by the intellectual elite. She lived in the convent the rest of her life, writing and teaching young girls music and drama. Her writings and critiques of misogyny gained the increasing ire of the of Bishop of Puebla, and in 1694 she was forced to sell her 4,000-volume library as well as musical and scientific instruments. Rather than be censured, Sor Juana dedicated the remainder of her life to charity work with the poor and died in 1695 after caring for her fellow sisters that were ill with the plague.

Despite being a nun, Sor Juana’s love poems expressed desire for women. She wrote passionately about love and sensuality. The first published collection of her poetry was published by Vicereine Marie Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga. There is speculation that the two had a romantic relationship, given their extremely close friendship, the woman’s name in the poetry, and that the Vicereine is the one who had possession of these love poems and ultimately had them published. Regardless of the extent of their actual relationship, the beauty and ferocity with which she writes makes her desires very clear, as seen in the poem below:

“Don’t Go, My Darling. I Don’t Want This to End Yet” (translated by Manrique and Joan Larkin):

Don’t go, my darling. I don’t want this to end yet.

This sweet fiction is all I have. Hold me so I’ll die happy, thankful for your lies.

My breasts answer yours magnet to magnet. Why make love to me, then leave? Why mock me?

Don’t brag about your conquest— I’m not your trophy.

Go ahead: reject these arms that wrapped you in sumptuous silk.

Try to escape my arms, my breasts— I’ll keep you prisoner in my poem.

Another beautiful example is entitled “My Lady” and can be found here: My Lady

Sources:

- “Juana Inés de la Cruz.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juana_In%C3%A9s_de_la_Cruz

- “Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Mexican poet and scholar.” https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sor-Juana-Ines-de-la-Cruz

~Rani Indrakshi (she/her)

June 6- The Bhagavad Gita: Krishna & Arjuna

The Bhagavad Gita is a 700-verse Hindu scripture that is part of the epic Mahabharata, dated approximately to 2nd century BCE. Considered to be one of the holy scriptures for Hinduism, the Gita documents the conversation between Krishna and Arjuna before the epic battle of Kurukshetra. The climax of the piece comes from the setting; Krishna and Arjuna are literally between the two armies as they talk, both sides waiting for Arjuna to blow his horn, which will start the battle. In the Gita, Krishna is the eighth human avatar of the god Vishnu, who only sends down an avatar when the world requires immediate divine intervention to ensure that good triumphs over evil. In this instance, Krishna teaches the great warrior Arjuna how to know what to do when faced with conflicting duties. Arjuna’s social obligation is to fight all injustices. Given this, one can argue that depriving queer people of the rights enjoyed by non-queer people is an injustice that ought to be opposed by anyone who aspires to follow in Arjuna’s footsteps. We can learn much about progressive spirituality through ascertaining the proper application of the Gita’s timeless teachings to contemporary life.

According to the Gita, every human is supposed to achieve four goals to have a complete life. They are Dharma, Artha, Kama, and Moksha. Dharma does not have an exact translation in English, but its closest translation is probably that of duty. These duties differ based on a person’s status and are supposed to be followed religiously. Artha roughly translates to making wealth. This does not inherently mean material wealth but rather creating value or increasing the value of something that you have been given. Kama means enjoyment or pleasure, including physical intimacy. Most important to note is that there is never a limitation of gender provided in the scripture when discussing Kama. Even enjoying the benefits of your wealth comes under kama. Moksha means liberation from the cycle of life and death. Even though this is somewhat a rare occurrence, this is the ultimate goal to have.

While the specific issue of gay marriage and queerness never explicitly comes up in the Gita, a careful study of the text can reveal implicit principles that support an inclusive, spiritually oriented society. In the text, Krishna points out that any sexuality should not be against religious principles: “I am the strength of the strong, devoid of passion and desire. I am sex life which is not contrary to religious principles, O lord of the Bharatas [Arjuna]” (BG 7.11). Throughout their conversation, Krishna encourages Arjuna to act according to his nature, both spiritually and materially. Since the Gita’s teachings are universal, the same must apply for any eternal spiritual being who identifies as being gay, trans, etc., in this or any other lifetime, due to contact with the three qualities of material nature.

The Gita also tells us that the four social orders of human society are “divided according to the qualities one acquires and the actions one performs. You should know that, although I am the creator of this system, I have no position within it, for I am eternally transcendental to such qualities and actions” (BG 4.13). Everyone’s primary need is the opportunity for spiritual advancement. To focus on spiritual advancement, we need to first obtain peace within. According to renowned Yogi Hari-kirtana das, prior to that, it is reasonable that some of our material needs must be met, including basic human rights such as the right to self-determination in balance with reasonable social obligations, the right to share our lives and love those we choose to share it with, access to education that matches our potential and medical care that matches our needs, and equal opportunities to work in accordance with our natural talents (Hari-kirtana das, 2022). He goes on to say that “If the institutions of a society systematically deny any of these basic human rights to people based on race, gender, nationality, or any other temporary material designation then it fails to live up to the Bhagavad-Gita’s standard for a society that protects and supports the progressive spiritual progress of all of its citizens” (Hari-kirtana das, 2022).

The primary message of the Gita is found in the universality of its conclusion, specifically, that all relative dharmas are inferior to the one ultimate dharma, which is a complete and fearless surrender, motivated by nothing other than love. Perfectly put, “… a truly spiritual society functions like a house in which the whole world can live” (Hari-kirtana das, 2022). The Bhagavad-Gita promotes a message of transcendental inclusivity in pursuit of the spiritualization of human society.

Sources:

- “The Bhavagad Gita.” https://human.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Literature_and_Literacy/Book%3A_Compact_Anthology_of_World_Literature_(Getty_and_Kwon)/3%3A_India/3.1%3A_The_Bhagavad_Gita

- “What Does the Bhagavad-Gita Say about Gay Marriage?” Hari-kirtana das, 2022, https://hari-kirtana.com/gay-marriage-in-the-bhagavad-gita/

- “A rare conversation between Krishna & Arjun” (image). https://www.pranayam.eu/blog/yoga-lifestyle

~Lady Aisha bint Allan (she/they)

June 5- Maddalena Campiglia

Maddalena Campiglia was a poet from the Veneto region of northern Italy. Born in 1553 to a “non-traditional” couple (her parents were both noble widowers living together out of wedlock,) Campiglia married before she reached the age of 25, at which point she would have found herself the recipient of a significant fortune from the dowry set aside for her had she not been forced into matrimony. The marriage was a “matrimonio bianco,” (translated literally, a “white marriage,” one that is not consummated and does not produce children) and functionally ended in 1580 when she returned to the home of her parents.

This is the point at which Campiglia turned her attention to writing, producing religious reflections, fables, and poetry. She wrote extensively on the theme of virginity, which she described as the “sole feminine possession which allowed her an escape of the canonical roles of wife, widow, and nun” (Aldrich & Wotherspoon). She is also credited with writing Flori, favola boscareccia, one of the earliest known female-authored pastoral plays in print (a distinction shared with Isabella Andreini’s Mirtilla, both published in 1588.) Flori tells the story of a nymph of the same name who is mourning her dead lover, another female nymph. While it is unknown if the play was ever produced for an audience, an appendix included in some of the printed editions makes note of the “unease felt by a few readers regarding its portrayal of female-female desire” (Maury Robin, Larsen & Levin.)

Campiglia’s most overt statement about her affection for women comes in the form of her poem Calisa: Egloga, written on the occasion of the marriage of Isabella Pallavincini Lupi’s son. Isabella could well be considered Campiglia’s muse, with the poet having written several sonnets praising her physical and spiritual beauty, one forming an acrostic of Isabella’s name. The Egloga provides a passionate defense of lesbian love, with the nymph Flori appearing again, this time in love with another nymph, Calisa, clearly identifiable as a stand-in for Isabella. The poetry includes the line “Donna amando pur Donna essendo,” or in English, “loving a woman while being a woman.”

Campiglia died in 1595, and as per the request in her will, was buried alongside Giulia Cisotti, abbess of the convent of Araceli and another woman with whom Campiglia was closely linked.

Sources:

- Who’s Who in Gay & Lesbian History by Robert Aldrich and Garry Wotherspoon (2001)

- Encyclopedia of Women in the Renaissance: Italy, France, and England by Diana Maury Robin, Anne R. Larsen, and Carole Levin (2007)

- “Maddalena Campiglia,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maddalena_Campiglia

- “’Woman loving while being woman’: Maddalena Campiglia (Vicenza 1553-1595),” https://www.culturagay.it/biografia/100

~Maistresse Mariette de Bretagne, OP (she/her)

June 4- King Hyegong

King Hyegong was the last king of the Royal Middle Family of Silla. He was born in 758 and took the throne at the ripe age of eight years old. Between both his age and lack of experience, his mother, the Empress Dowager Manwol, acted as his regent. Tragedy sadly struck and he was assassinated in 780, at just twenty-two years old. Depending on the source, the reasons for his assassination vary; political turmoil raised by the Empress was one potential reason the young king was assassinated. According to the Samguk Sagi, a historical record of the Three Kingdoms of Korea: Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla, “King Hyegong ascended the throne at a young age, and when he grew up, he was immersed in music and women, and there was not moderation in playing.”

Historical record points to much of King Hyegong’s behavior being categorized as effeminate. He’s often described in the Samguk Yusa, a companion history to the Samguk Sagi, as, “…a man by appearance but a woman by nature…”and according to Dongsa Gangmok, a Korean history book written by Ahn Jeong-bok about the Joseon dynasty, Hyegong’s reign is described as, “peculiar, for it was said that the king became a man as a woman, and for the king played with girl’s toys as a child.”